Why do we sing in many languages during our prayer?

Sometimes when we have new visitors to our community prayer, or we organise a prayer elsewhere, I’m aware that our use of many different languages in the songs may appear a little strange to those who are not used to it. It seems natural to us, with a background in Taizé, but it is one of the few areas in which we actually deviate from the Taizé Community’s suggestions for conducting prayers elsewhere.

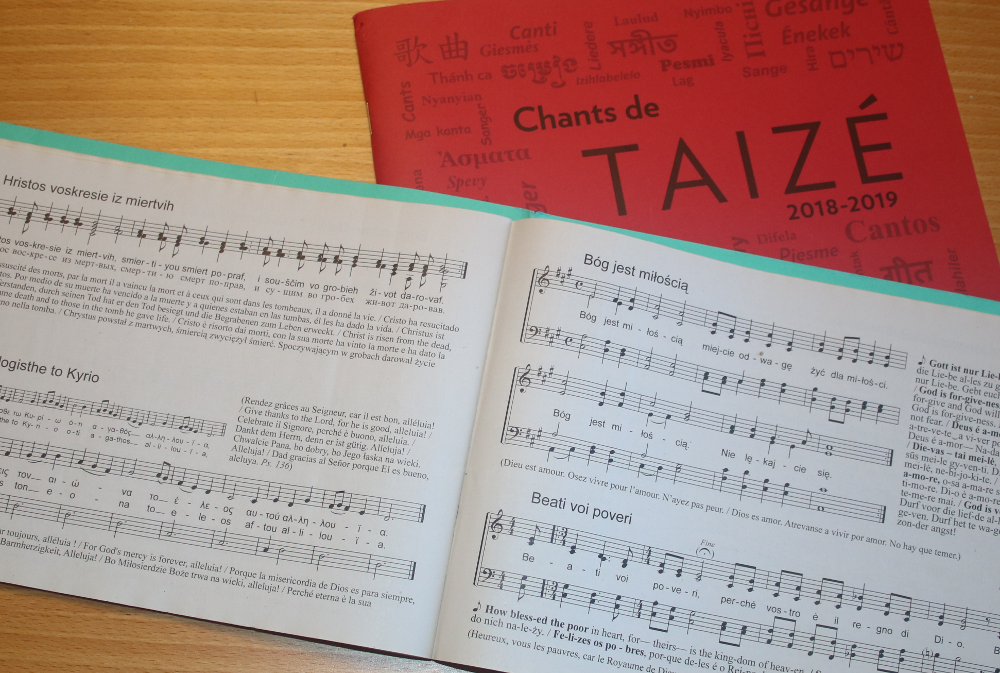

The introduction to the Taizé songbook, entitled “How Can We Keep On Praying Together?” contains various proposals, most of which we follow, for example with regard to participants facing in the same direction, “as a way of expressing that our prayer is directed not to one another but to Christ”. However, one suggestion is at odds with our practice, asserting that:

“Songs in different languages are appropriate for large international gatherings. In a neighbourhood prayer it can be disconcerting to use foreign languages without a particular reason, and so it is better to choose songs in English or the local language, or possibly in Latin.”

So why would a small community in the North of England, where all current members speak English with native proficiency, make use of a wide range of languages, most of which we barely understand, if at all, beyond the few words we use in song? If we are told that it may be disconcerting, are there perhaps valid reasons why it is good for us to be mildly unsettled?

In pondering these questions, three significant benefits stand out in my experience of many years of using these songs in prayer:

- In using many languages, we are constantly reminded that we are a part of something much larger and more significant than national borders, or even the English-speaking world. We recognise the Church not as a national organisation, but as a thoroughly international community, which mostly doesn’t speak English. It is too easy to forget that English is not a ‘native language’ of Christianity and our primary texts are in translation. In the light of this realisation, we express our desire to grow in this community, in solidarity with others worldwide.

- We gain new and different perspectives on the simple realities we express in song by seeing them through various linguistic lenses, with differing nuances and emphasis in expression. This is enriching in allowing us to think outside the linguistic limitations within which we spend most of our time. This approach can also be applied in reading; simply studying a short Bible passage in a different language, even if it is a struggle to understand at first, can render a completely fresh understanding of an overly-familiar text.

- For some of us, an excess of words during a time of prayer can be distracting. From my own subjective experience, singing in a language other than my own can help by reducing the intrusiveness of words into that space of divine encounter. The short, repetitive chants are an aid, rather than an end in themselves. Constantly hearing words in our own language can make it more difficult to move beyond the simple words we are singing. Familiar words which we understand the meaning of, but are expressed in a language which is not our own, can perhaps more easily slip into the background while our meditation continues elsewhere.

But isn’t it terribly elitist or pretentious to be routinely singing in French or Latin? There is the assumption that a knowledge of foreign languages is the preserve of the privileged. After all, the media made a fuss about Princess Charlotte speaking “some Spanish” by the age of 3, quickly exaggerated as being “already bilingual”. It’s easy to imagine that knowledge of other languages is a nicety reserved for the wealthy.

However, looking at the broader society in which we live, this assumption could not be further from reality. True bi- or trilingualism is taken for granted among the majority of immigrant families and asylum seekers. It is a basic survival skill, rather than an ornate flourish on an expensive education, although the media may not celebrate this as it does a few foreign words from a royal infant. The possibility of being able to mostly go about our daily lives with only one language is more of an anomaly than the norm once we look beyond English-speaking countries. May we always remember, as we sometimes stumble over the difficult words of a less-familiar song, that this is a small insight into the daily reality of many in our society.

Indeed, one does not simply learn a language. You develop bit by bit and in some way, opens your mind.

On the other hand making the effort to pray in another language can, —if you are honest—, make you humble enough to understand that God isn’t moved by the beauty of our words but by the love in our hearts.